Features / Education

Tackling persistent absence in school and rebuilding belonging

Every morning, Chris Barratt, senior principal of Summerhill Academy in St George, stands at the school gate. After nearly two decades in education, this simple routine remains his favourite part of the day.

“As much as possible, it’s me on the gate,” he says. “That interaction – it’s one of the most important parts of being a headteacher.”

The school gates are the frontline of a strategic and human-centred approach to creating a positive school culture. Post-pandemic, persistent absence—defined as pupils missing ten per cent or more of school—has become a national concern.

is needed now More than ever

But at Summerhill, a school serving a richly diverse community, Barratt and his team are proving that solutions lie not in punishment, but in creating a culture of belonging. “It’s getting them across the threshold in the first place,” Barratt says.

He emphasises that once pupils are in school the key is making them feel safe, valued and like they belong. Summerhill’s approach starts with one key question: What makes children want to come to school?

Barratt is candid that if a child’s experience of school isn’t positive—if the curriculum doesn’t speak to them, if they don’t feel seen, if their parents didn’t value school themselves—it’s harder to make the case.

So the school focuses relentlessly on building an environment that feels safe, joyful and purposeful.

From consistent routines to culturally sensitive policies and an engaging curriculum, everything is designed to help children feel they are part of something worth showing up for.

“We talk a lot about building positive efficacy. When children feel that, they start to build a relationship with school that’s self-sustaining.”

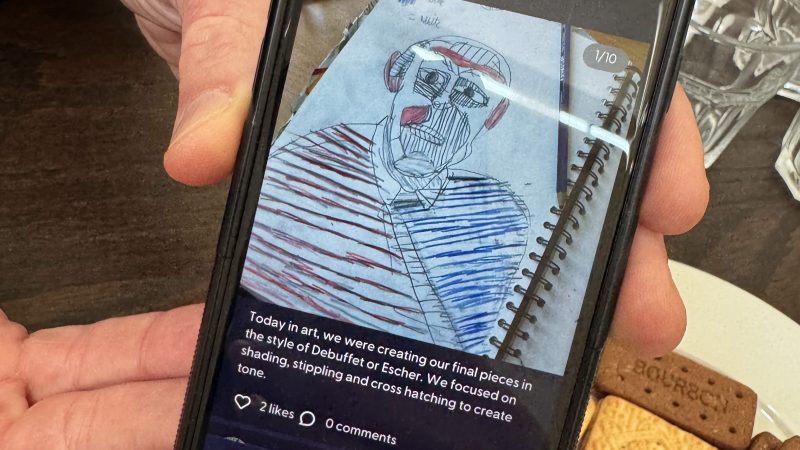

This includes a strong emphasis on communication. Summerhill uses a closed digital platform called Class Dojo to keep parents engaged with daily updates and photos from the classroom.

Instead of when parents ask their children ‘What did you do today?’ and get nothing in return, they get a real insight into their day.

For students, “parent and teacher communication can be a burden if not done right,” says Barratt.

With higher levels of anxiety or social and emotional needs there is a massive emphasis on ‘getting them over the threshold’.

One of those tactics is a space called ‘Base Camp’, a calming, structured room where a small group of identified children start their day.

Here, trained staff greet them, offer breakfast and ease them into learning through low-stress activities. By 9am, most of the children have transitioned smoothly into their classrooms. “We want every child to be with their peers,” says Barratt.

Class Dojo has channels covering the whole school, as well each individual class – photo: Hannah Massoudi

Last term, the school went further, with the implementation of the Department for Education’s trial of universal free breakfast for all pupils. They open the doors 30 minutes earlier and have seen a nearly 50 per cent uptake.

Barratt is clear: persistent absence can’t be tackled in isolation. “It has to be part of a whole-school multiagency approach,” he says.

Summerhill’s staff are trained to spot early signs of emotional distress and five members are certified youth mental health first aiders.

The school also buys in support from Bristol City Council’s attendance officers, who can step in when family situations—like transport issues or housing instability—become barriers.

Sometimes, attendance isn’t about the child at all. “Maybe the family moved to temporary housing far away.

Suddenly, the journey’s two buses and £10 a day.” That’s where education welfare officers help them unlock solutions.

“For me, good or bad attendance is a symptom of the school offer.”

Summerhill doesn’t wait for absences to become a pattern. Fortnightly, the leadership team meets with each year group’s teachers to discuss real-time data on attendance and progress.

Trends are flagged early, actions are defined and interventions are swiftly enacted. “The goal is prevention,” says Barratt. “We want to stem absence before it becomes a habit.”

This is backed by a curriculum designed to be spiral and cumulative, meaning children rarely miss something that won’t be revisited. “For most one-day absences, the learning catches up with itself,” he explains.

“But for repeated or prolonged absence, we have to know each child well enough to fill those gaps intentionally.” As part of the Cabot Learning Federation, Summerhill shares attendance strategies with 35 other settings through cross-trust networks.

Their trust-wide attendance lead ensures best practice is shared and scaled. Yet for Barratt, no system replaces human connection.

“We serve a community with 32 first languages, 17 ethnicities. Some families have experienced trauma or disruption. Our job is to be constant—to show up, to listen and to make school feel like it matters.”

Christine Townsend is a Green Party councillor for Southville – photo: Rob Browne

School attendance in Bristol has become one of the most pressing challenges facing education leaders post pandemic, with the city ranking sixth across England for persistent absences.

In January 2024 an attendance taskforce was set to find out why.

“We’re still dealing with the long shadow of Covid,” Christine Townsend the chair of the children and young people policy committee at Bristol City Council explains.

“There’s an entire generation of children who either didn’t get a proper start in school or whose education has been repeatedly disrupted.”

Bristol Futures, a citywide initiative focused on improving educational outcomes, has made school attendance a priority.

One strand of the programme, led by a local academy trust chief executive, seeks to break down the layers behind absenteeism—distinguishing between occasional absence, persistent absence and the more concerning severe absence.

While schools hold the initial responsibility, cases that reveal deeper social or emotional issues are escalated to children’s services.

“Children need to see their own lives and realities reflected in what they learn.”

“What we often see is that severely absent children were previously persistently absent,” she says. “It doesn’t happen overnight. We have to ask what’s going on in that child’s life.”

Sometimes, it’s unmet special educational needs. Other times, it’s pressures at home—financial hardship, mental health, or responsibilities such as young caring that go unrecognised.

“There are children whose families don’t even realise they’re young carers. It often takes an external person to notice and raise the flag.”

Post-pandemic, the effects are compounded. Townsend points to gaps in early years education, limited social interaction and fractured transitions from primary to secondary school.

“The impact for those children going through exams around 2021 will be different to a really young child of maybe two or three that’s now maybe in year one or two, but they didn’t have access to that kind of early years intervention at nursery education.

This shows up particularly around speech and language.”

The council is currently forming a task and finish group to focus specifically on Key Stage three (years seven to nine)—a group Townsend refers to as the “forgotten middle.”

These are children who were in primary school during lockdown but didn’t sit SATs and may have missed targeted support.

They want to understand who’s staying in school and why—and who’s slipping through the cracks.

In many cases, Townsend believes that school culture plays a vital role in whether a child feels welcome. She’s critical of punitive policies like zero-tolerance late marks or rigid uniform rules.

“If the first thing a child hears when they arrive is, ‘Why are you late?’ or ‘You’re you haven’t got the right uniform on,’ that’s really not going to encourage them to want to come again.”

Fining parents for term-time absences is an issue that is immediately brought up by the parents I speak with.

In response, Townsend says: “Parents need to feel that the school is part of their community as well, we don’t want to create fear and anxiety in the parents and push them away.

“I do think there’s a re-orientation about what education is for and what children need at this moment and possibly previous to COVID as well.”

Instead, she advocates for a more inclusive and emotionally intelligent approach to education.

That includes integrating mental health support—something she says remains chronically underfunded—and training teachers to recognise and respond to emotional needs.

Another concern is the pressure on public services. “All services have been stripped back. CAMHS waiting lists are enormous.”

There is no one size fits all solution but she suggests: “A redirection of that resource so that it becomes much more mainstreamed in educational settings around emotional support and resilience to create more of a whole child approach.”

The long-term vision includes improving inclusion, adapting the curriculum to reflect students’ lived experiences, as well as building areas within mainstream schools for those with special educational needs so that schools are better able to cater for a wider range of needs. and sharing best practices across all types of schools.

Townsend uses the example of producing resources: “Making sure those resources are quite engaging and that you’re taking account of children that might learn through their visual sense, others might learn through auditory sentences.

So ensuring that is the sort of good practice, that’s first quality teaching in classrooms, caters for that variety. And then you get more inclusion within that.”

Alfie became a pupil at Summerhill Academy in year three.

He once enjoyed school and continued to be a good learner and very sociable once he was in the building long enough, but there was always a noticeable level of anxiety that would return as every school year brought new teachers and new routines.

This slowly began to manifest in habits that were detrimental to his wellbeing: one year he would pick his skin and then another year he wouldn’t sleep.

His mum Lynnie Orzechowska, tried to tell him not to worry about it, but she says as he got older there was inevitably more of a push back.

While he never received a formal diagnosis for anxiety, his feelings around school got worse and as he transitioned into year six in September 2024 he became persistently absent.

The school stepped in and stepped up and now more than six months later, Alfie’s attendance is above the national average.

Lynnie explains how the support from the school turned his attendance around. Lynnie says: “I just needed that extra support from school and they were there.

“They initiated the support. It was one of the teachers once in the day and they were like Alfie’s really struggling today.

“I think it’s this. And she hit the nail on the head. She knew exactly what it was that was upsetting him and we resolved the situation.”

They suggested he have an autism assessment, which he had and the results were he didn’t tick enough of the criteria. Regardless they suggested ways in which the school could support him.

“He’s just seen and that makes the difference.”

Base Camp was one the things that the school identified would be beneficial for Alfie. As it turns out the stimulation of the busy classroom was too much for Alfie first thing in the morning and Base Camp provided that soft start.

He would colour or do homework. Someone was consistently on the gate to meet him everyday for at least six months.

She laughs as she says: “Come rain or shine, Chris (the school’s senior principal) is also out there, everyday, he’s present, so if anybody’s got any concerns, they could ask him.”

Alfie was also able to take advantage of an initiative called the Learning Lab. Lynnie explains that throughout the day, if ever it got too much for Alfie in the classroom, he was able to just walk out and leave the classroom and go to the Learning Lab, no questions asked.

This room is a quiet space open all day where pupils can take some time out to work on their own, with

the exception of whichever teacher is supervising the space and the small number of selected students.

The Learning Lab coupled with Base Camp has empowered those who are struggling with tools to regulate their emotions, which has in turn filled them with confidence and a positive approach to learning.

Alfie no longer uses the lab and very recently he decided he could walk in on his own.

To top off the resources on offer, before the beginning of each week or the first day back to term “we’d receive a message on Class Dojo from Alfie’s teacher, just saying we’re looking forward to seeing Alfie on Monday. This is kind of rough what we’re going to be doing.”

She says that the school has been “amazing” in taking the time to listen to both her and Alfie. While he now has the established routine and apparatus to lean on if needs be, Alfie will be moving up to secondary school – a whole new routine, teachers and pupils.

But Summerhill Academy is already across it. They’ve sent Lynnie links to websites to access external support and as he moves into the new term he along with a select number will have workshops tailored to transitioning

without anxiety.

“I hand on heart think that if they weren’t as engaged as they were, Alfie wouldn’t be at school.”

As she reflects on their Summerhill experience Lynnie says it feels like they prioritise their pupils’ wellbeing. She adds: “At no point has anybody said he needs to come into school because he needs to do his SATs or said he needs to get good grades.

“Nobody’s ever said anything like that. I feel like they want Alfie to come to school and be happy.”

This article is taken from the May/June 2025 Bristol24/7 magazine

Main photo: Hannah Massoudi

Read next:

Our newsletters emailed directly to you

Our newsletters emailed directly to you