Features / floating harbour

Bristol’s dockside cranes are ‘a love affair with our city’s skyline’

They chatter away, posing patiently while visitors from far and wide snap photographs. Sometimes they even dance for the adoring crowds.

Once upon a time, these cranes were merely part of Bristol harbour’s supporting cast but more recently they have taken centre stage.

Built by the renowned Stothert & Pitt of Bath and installed in 1951, these electric cranes became an important part of the Bristol skyline.

is needed now More than ever

But they were by no means the first cranes surrounding the docks. The first documented crane is in the late 1400s, when the widow of a wealthy merchant bequeathed funds to have it installed.

“It had a giant hamster wheel that men could walk around in to lift things out of the holds of ships,” said historian Eugene Byrne.

The first detailed map of the city was published two centuries later, and would include the labelled image of a crane on what today is Welsh Back.

“A thousand years ago, Bristol springs up around a bridge over the River Avon and becomes one of the most significant ports in England,” Byrne said.

“Transporting anything by road was expensive, difficult and hazardous, so water transport was important.

“By the 19th century, ships are getting bigger, there’s very little danger of Vikings invading and that winding tidal River Avon becomes more difficult to negotiate, which is why we ended up with Avonmouth docks on the coast.”

Smaller ships may have mostly been coming into the docks by the Second World War, but Bristol was still very much a working harbour when the city was bombed extensively during German air raids.

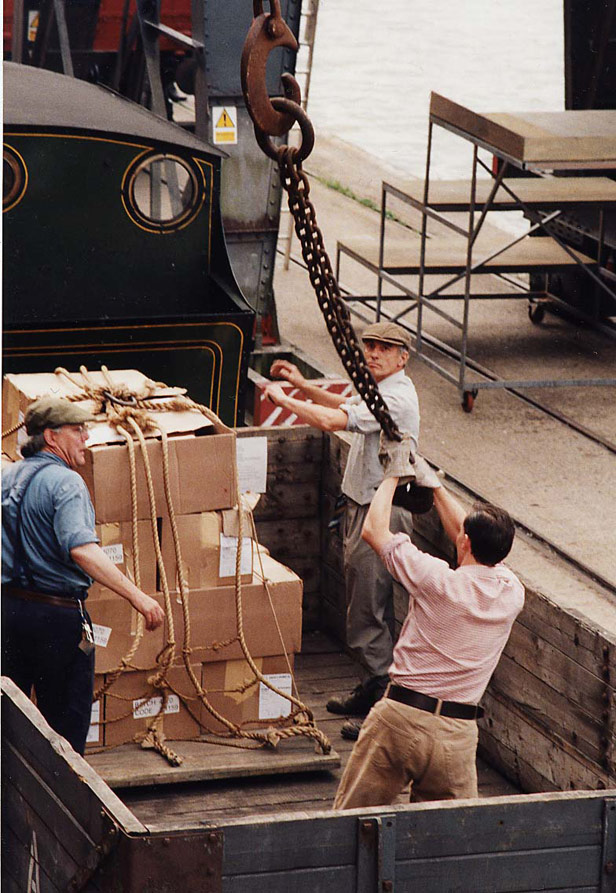

The cranes at Princes Wharf in 1972 – photo: Bristol Archives

The electric cranes were installed during the post-war reconstruction. During their 25-year tenure assisting dock workers, most of the Princes Wharf cranes had a one-ton capacity, upgraded to three tons so they could handle shipments of Guinness coming in from Dublin, according to a 2020 lecture by Andy King, one of the people instrumental in the cranes’ return to glory.

With the prevalence of metal cargo containers and the giant ships that carried them, the days of men manually hauling goods off the docks were dying, according to Byrne.

There were several stumbling blocks for the city docks such as the lack of space for container cargo and the construction of the Royal Portbury docks across from the existing infrastructure at Avonmouth – both well-suited to large ships thanks to their situation on the Bristol Channel.

Through the mid-1960s, “we had a philistine council who didn’t give a toss about the harbour”, John Grimshaw told Bristol 24/7 in 2022. Though the industrial harbourside was still in use, “the council basically continued to consider the docks as wasteland”.

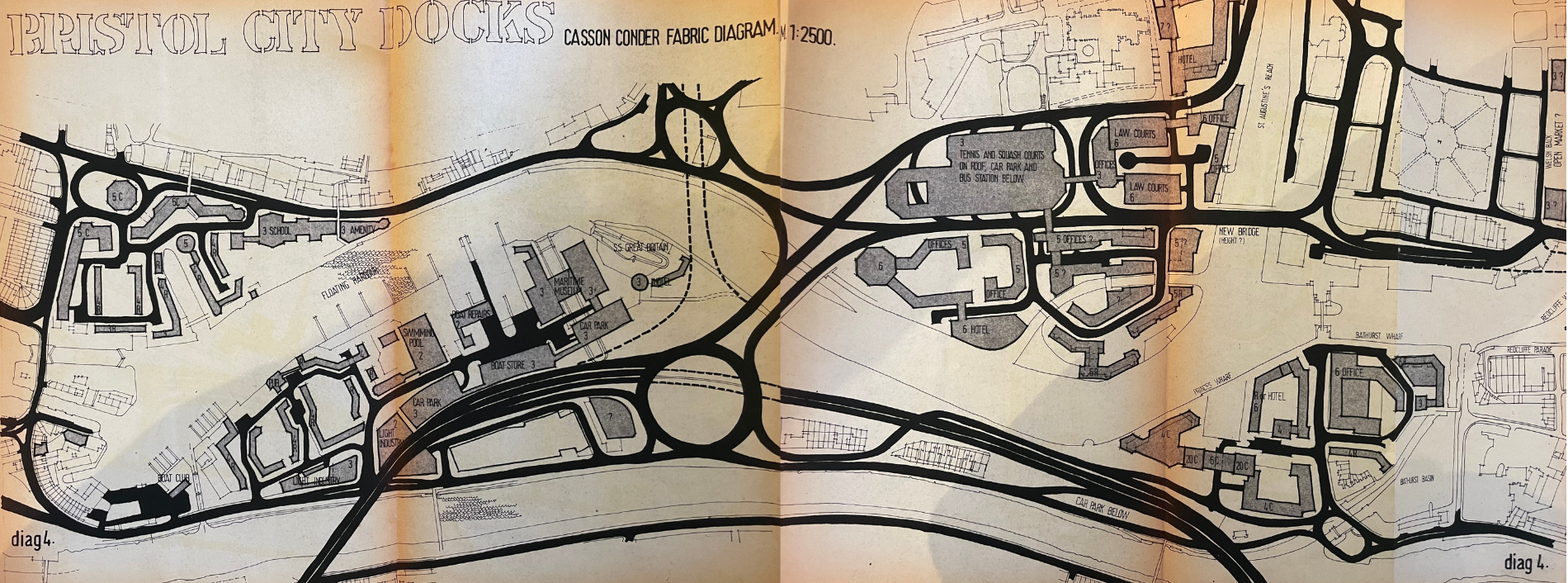

A plan for the docks from October 1973 – courtesy of Jean Macfarlane

Plans to fill in the docks and run large roads through thankfully managed to be halted by activists including Grimshaw but as the docks closed to shipping, 40-odd cranes in the harbour began to be scrapped or sent over to Avonmouth.

“We were losing this spectacular skyline,” said Grimshaw.

In the words of King, the group quickly deployed the 1970s equivalent of crowdfunding. “I got £4,500 in cash and went over to Newport to the scrappy, put it on his desk and I said, ‘I’m buying them back again’,” said Grimshaw.

A few years later, the council decided not to sell off three of the rough-looking cranes for scrap to invest in a coat of paint for the fourth. They sat untouched until they eventually became part of the Industrial Museum (now M Shed) collection in 1989.

The cranes outside M Shed sometimes even talk to each other – photo: Reecy Pontiff

Andy King, who sadly died in 2021, joined the team at the Industrial Museum in 1981, and was instrumental in creating the harbourside as we know it today.

His know-how, enthusiasm and community-minded vision are the reason for the resuscitation of the cranes, as well as the steam train and several historic boats that delight visitors along the waterfront.

Much of his success laid in his ability to assemble and galvanise a network of technically inclined volunteers to take on these extensive rehabilitations, according to Byrne.

A hit at the Bristol Old Vic would trigger the first crane restoration. The play Up the Feeder, Down the Mouth and Back Again was written by playwright ACH Smith based on extensive interviews with people whose lives had been tied up with the docks.

When the play opened in 1997, Smith gave out free tickets to everyone he had interviewed. “Many in the audience had seldom or never been to a theatre. They shouted out, ignoring the shushing,” Smith wrote in the Bristol Review of Books in 2011. “Every night, elderly men were in tears.”

A couple of years later, a few scenes from the play were performed in an old railway car by a local youth theatre during a festival. This got director Andy Hay’s gears turning and he approached King about putting up a revival of Up the Feeder on the actual docks.

“We readily agreed and committed to having one crane ready to play a part in the production,” King said in his 2020 lecture.

“We just managed it – jerry-rigging a power supply, overhauling only the most essential elements and learning how to drive it.”

The massive rolling cargo doors of the L Shed warehouse trundled back to reveal the bustle of the docks recreated by actors. The steam train and antique trucks chugged by.

The thousand-tonne cargo ship, Lucy, was the first cargo vessel to visit the wharf since 1974 and was almost certainly the biggest prop used in any UK theatre nationwide that year, with one of the cranes also operating for the first time in decades.

The revival of Up the Feeder booked out its entire run before the opening night, with 20,000 audience members seeing the play.

“To this day, people tell me how much they enjoyed it or how cheesed-off they were at not getting in,” said Smith.

A scene from the theatrical production Up the Feeder, Down the Mouth and Back Again, staged at Princes Wharf in 2001 – photo: Bristol City Council

After Up the Feeder, King’s team began repairing the cranes in earnest and by the time the Industrial Museum shut down in 2006, they had two in full working order.

The cranes were used to remove large artefacts from the space before renovation began for the opening of the M Shed and would later hoist masts for tall ships and boilers for steam trains ready to be repaired.

They would pick up a new skill for the 2015 Docks Heritage Weekend: synchronised dancing. “They had recently finished restoring the third of the cranes, so it was a beautiful opportunity for them and their volunteers to get to do something different,” said artist Laura Kriefman, creator of the Mass Crane Dance.

“Andy King was such a gentleman. He and all of his team had such an openness to the collection being explored, showed off and celebrated.”

The cranes were lit in an array of colours and performed their ballet to the sounds of a live band banging out Bhangra arrangements of sea shanties.

“It was like watching elegant giraffes,” Kriefman said. “It was a slow and graceful show.”

According to Kriefman, the cranes’ choreography had to be both stupendous and safe: “We had to work out what would allow us to show off their maximum movement, including traveling along the quayside and lowering the hooks, that luffing and jibbing, and we had to make sure that we wouldn’t smash into a building or create too much momentum with the hooks.

“That’s the main consideration with cranes: how big a range have you got and what do you need to avoid hitting?”

Each crane was operated live during the show by King and his team as Kriefman called out the sequence of movements to the crew via radio.

Having put out little information about the event and up against a televised Rugby World Cup final, “we were expecting maybe a couple of hundred people”, Kriefman said. “But 10,000 people showed up!”

“I was blown away by the reaction. It’s a love affair with our skyline. It’s a love affair with the city.”

This event was a test-run for similar projects. Kriefman choreographed at 140-tonne crane dance for Arcadia’s Pangae stage at Glastonbury 2019 and was in talks about similar projects in numerous locations before Covid.

“The more we talked to other operators and crane sites and decommissioned sites around the world, the more we saw that it’s really rare to find dockside cranes which are still working,” she said.

“Ever since they were saved in the 1970s, everything that’s been done to bring them back to life again has been a community effort,” King told the BBC in 2020. He estimated that 55,000 volunteer labour hours had been invested in the cranes at that point.

In 2022, the cranes were legally preserved when they were bestowed with a Grade II listing. But King would never hear of the listing of his dear cranes; he died from cancer shortly after his retirement in 2021.

The week of his passing, the jibs of two of the cranes were crossed in a poignant mark of respect. Their caretaker would be pleased to know that the cranes have still found new projects to take on.

Crane 29 had a luxury treehouse built around it in 2017. Thousands of potential guests registered for the lottery to stay in the temporary Canopy & Stars property but only 260 people had the chance.

These days the cranes themselves have become nostalgic. For years now, two of them have a little chat with each other, reminiscing about all the many things they have seen.

During Docks Heritage Weekend on Saturday and Sunday, visitors will be able to tour the driver’s cab on a crane; while train and crane driving experiences take place from October 13 to 17

Main photo: Reecy Pontiff

Read next:

Our newsletters emailed directly to you

Our newsletters emailed directly to you