Features / Architecture

‘Fascinating textures and abstract forms make car parks so interesting’

Multi-storey car parks might not seem exciting at first glance but they’re often striking examples of bold brutalist architecture.

One of the features of a new exhibition celebrating Bristol’s brutalist buildings is a set of photographs of car parks by Andrew Eberlin. His camera picks out the fascinating textures and abstract forms that make car parks so interesting.

“My project was prompted by plans to replace the Rupert Street car park with an accommodation block,” Eberlin says. “This isn’t any old car park thrown up carelessly. It’s Bristol’s first multi-storey car park and the first in the UK to feature a continuous spiral parking ramp.”

is needed now More than ever

The Lex “multidek” on Rupert Street was described when it opened in 1960 as “more than a car park”

The architect of Rupert Street car park was Swiss-born Rudolph Jelinek-Karl who trained in Munich and Paris, and worked in Algeria. He came to Britain in 1936 at the height of the Art Deco era and after World War II, he specialised in car parks.

The Rupert Street car park’s rounded, coiled form suggests a great sleeping snake or dragon – if you’re romantic and imaginative, that is, which perhaps surprisingly fans of brutalism often tend to be.

550 cars were able to be parked on the upper floors, with a car showroom, workshop and a petrol station on the forecourt

Across town, NCP Prince Street was designed to serve the hotel next door by Kenneth Wakeford Jarram & Harris in 1966. It is, believe it or not, much admired by fans of post-war architecture.

Prince Street car park’s rectangular bulk is broken up by mesmerising saw waves and diamonds that cover its bulk. In summer sunlight, the shadows do interesting things. In winter, it sounds a chilly European note on the harbourside.

It has a slight resemblance to another brutalist icon, the Welbeck Street car park in London’s Marylebone which was sadly demolished in 2019. The Prince Street car park feels more precious in that context, as a surviving example of a type.

Prince Street car park is one of Bristol’s best known examples of brutalist architecture

There are several other notable Bristol car parks. The massive one at Trenchard Street dates from 1966-67 and reportedly has three miles of car parking space. It looks all the more imposing because it’s built into a vertical hillside.

The car park at Castlemead is a relic of the 1970s and the later period of brutalism, before it gave way to post-modernism.

The car park next to Castlemead “is a relic of the 1970s” says Ray Newman

Car parks are not abstract sculptures, however. They represent the mid-20th-century tendency to prioritise motor traffic over pedestrians and over nature.

In a bike-friendly, green city like Bristol especially, you might think it would be good to see them go.

Plans are afoot to demolish Nelson Street car park

“They’re a reminder that once cars were the future,” says Eberlin.

“They promised independence, flexibility and the romance of the open road. Until everyone got a car, that is, and they became part of the problem.”

West Ene car park dominates the top of Jacob’s Wells Road

Car parks are often unpleasant places to inhabit, too, full of fumes, strange stains and dark corners. There’s a reason so many crime and espionage dramas use them as the settings for illicit rendezvous or for murders.

But there have been successful projects to reclaim these buildings, turning them into covered markets and art spaces.

This can be an effective way to preserve these imposing physical reminders of the disappearing 20th century while acknowledging that their original purpose – maximising space for cars in our city centres – is no longer desirable.

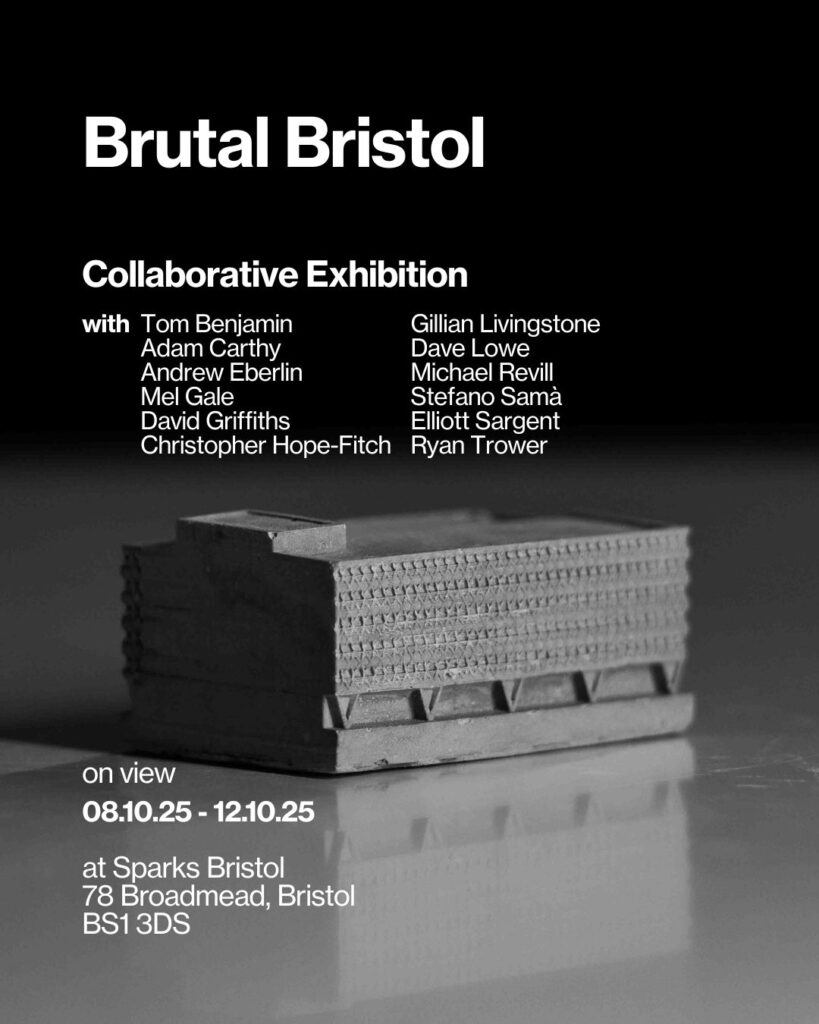

This article originally appeared in the Brutal Bristol zine. Andrew Eberlin’s photos will be shown at the Brutal Bristol collaborative exhibition from October 8 to 12 at Sparks in Broadmead.

All photos: Andrew Eberlin

Read next:

Our newsletters emailed directly to you

Our newsletters emailed directly to you